Brandon Theesfeld’s voice cracked as he read his statement to the family of Ally Kostial, the girl he finally admitted he killed.

Brandon Theesfeld’s voice cracked as he read his statement to the family of Ally Kostial, the girl he finally admitted he killed.

“I wish I could take it all back but I can’t… I have asked God to forgive me,” he said. “I hope you can find it in your heart to forgive me.”

Theesfeld pleaded guilty in the shooting death of the Ole Miss coed on Friday morning, and the facts began to answer a lot of the questions asked by so many in the case almost as clearly as Theesfeld’s “Yes sir,” when the judge asked if he had killed Kostial.

A damning trail of digital evidence had led investigators straight to Theesfeld after Kostial’s body was found at a picnic table in rural Lafayette County, according to Assistant District Attorney Mickey Mallette.

Kostial and Theesfeld had dated off and on, but it hadn’t become serious at any point. According to Theesfeld’s attorney Tony Farese, Kostial was more interested in the relationship than Theesfeld was.

But it was mid-April when Kostial texted Theesfeld in a state of panic with a photo of an inconclusive pregnancy test.

For the next three months, Kostial would reach out to Theesfeld, asking to meet face to face, and he would deny her or cancel at the last minute.

According to the prosecution, Theesfeld’s internet search after hearing from Kostial that she might be pregnant showed him researching abortion services and abortion pills. He also told her via text that he wasn’t ready to be a father. From there, they stopped seeing each other in person and their communications were strictly electronic, Mallette said.

As time passed, Kostial became more and more insistent to meet with Theesfeld. He stopped responding, telling her basically that talking wasn’t necessary.

“He showed little or no interest in meeting with her in person,” Mallette said.

Mallette said that in July 2019, Theesfeld went home to Dallas to talk with his father. On the way back, he posted a photo to social media that showed his 40 caliber Glock model 22. The caption stated, “Finally bringing my baby back home.”

According to law enforcement, research history on his computer showed internet searches for — among other things — silencers and suppressors, hollow point ammunition, tactical facemasks, and how Ted Bundy lured his victims to death.

Soon Theesfeld reestablished contact with Kostial on July 17 as he returned to Oxford, saying he was ready to meet with her. He asked how private her house was. On July 19 after some texting, he texted at 9:06 p.m. and told her to let him know when she was home from the bar.

Security video from the night Kostial was killed showed her leaving a bar on the square at 11:52 p.m. Roughly an hour later, Theesfeld’s truck could be seen on a different camera headed to her house, and then away from it a few minutes later. Police would find later that Theesfeld had been drinking, but he was also high on cocaine.

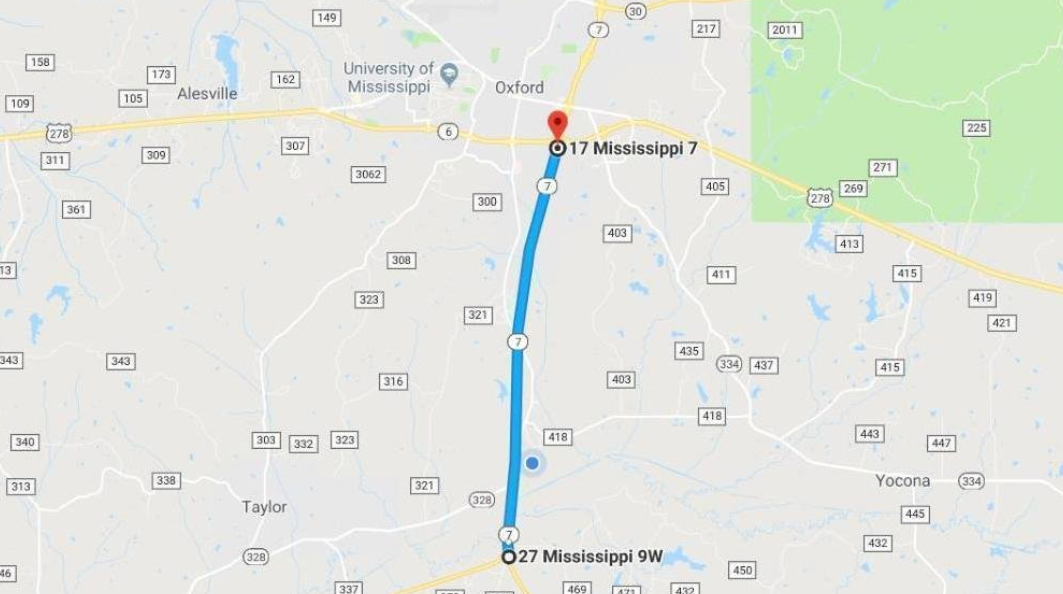

Investigators said both of Kostial’s and Theesfeld’s phones pinged on the way out to Lake Sardis, where her body was later found. Between 2:15 and 2:30 a.m., a resident of the area told police they heard gunshots.

Both phones pinged as leaving the area a little later, but Kostial’s was eventually discarded and has yet to be found. Theesfeld’s showed him arriving back in Oxford at 3:28 a.m., and at the same time, his search history showed “listen to police scanner.”

After being seen on camera at a gas station in Batesville around 7:45 a.m., Theesfeld texted a friend to see if he could stay with him for a little while because an exterminator was at Theesfeld’s apartment. That, Mallette said, wasn’t true.

At 8:18 a.m., Theesfeld searched “Sardis MS news.” He would stay at his friend’s apartment for the next several hours.

Shortly after 10 a.m. on Saturday, July 20, Ally’s body was found by a deputy on patrol. She was left at a picnic table along with several empty beverage cans and 11 shell casings. The location of that picnic table corresponded with the location of both her phone and Theesfeld’s from the early morning hours. Her purse was found about 1/3 of a mile away.

The next morning Theesfeld went to visit another friend, using the same ruse of an exterminator at his apartment. That friend told police he saw the gun that would prove to be the murder weapon. That same day, police contacted Theesfeld and asked him to come in and answer some questions, and he agreed.

When they called him back, Theesfeld told them he had been drinking and wasn’t comfortable coming in. He said he would come in on Monday, but instead fled to Memphis. When police caught him there, he had his Glock pistol with him.

Forensics tests were run on the gun and bullets fired from it matched the casings found at the scene as well as the bullet fragments found in Kostial’s body.

Police served a search warrant at Theesfeld’s home and found a 2 page letter written on a legal pad. It was intended for his parents, Mallette said. In it, Theesfeld admitted that he’d always had “bad” thoughts.

“Dear Mom and Dad, I’m not a good person, and it’s not your fault. Something just doesn’t work,” it read. “…I think this is the end for me. I’m either going to prison, or I’m going to die.”

Standing in front of the judge in his orange jumpsuit between Farese and co-counsel Swayze Alford, Theesfeld looked small as his plea was accepted. He appeared to be staring at the ground as Kostial’s parents’ statements were read to the court by Mallette.

“We take comfort in the fact that Ally will never be defined by the way she was ripped from our lives,” Cindy Kostial wrote, adding that she’ll be remembered for her goodness and light.

Cindy Kostial’s letter detailed her daughter’s life as their perfect firstborn who loved reading, photography, nature, and Ariel the Mermaid. Ally’s mother spoke of her athletics, accomplishments, art, how she loved sunrises and sunsets, and how she went on vacations to far away places and gave to the communities there.

But so much has been taken away, she wrote.

“Our holidays will never be the same. Ally absolutely loved everything about Christmas,” Cindy Kostial wrote. Addressing Theesfeld, she wrote: “I hope every time your cell door slams shut, you’re reminded of the beautiful life you took from all of us.”

Ally’s father Keith Kostial wrote of how she was always smiling, probably up to her last breath, he said.

Ally was excited to go to Ole Miss and make friends and had loved her life there, Keith Kostial wrote. He said she loved to find the beauty in things, and that he still sees beautiful things and thinks, “Ally would love this too.”

“But there will be no graduation… he shot her several times, she hurt, she bled, and he left her for her body to be found the next morning.”

Theesfeld’s voice was stoic at first as he read his statement apologizing to Kostial’s family and lamenting that his actions couldn’t be undone. But when he asked for their forgiveness, the emotion came through. Both families, on opposite sides of the courtroom, barely moved.

After Theesfeld had been taken away by the Mississippi Department of Corrections, Farese said they entered the plea because the state had sufficient evidence to prove that Theesfeld was responsible for Kostial’s death, but lamented the senseless loss of both young lives.

“The evidence shows she was not pregnant,” Farese said. “But that was part of the underlying theme in the relationship.”

Theesfeld will spend the rest of his life in prison.