Green’s granddaughter Juanita Hollinghead told their story at a recent ceremony to honor their lives by dedicating part of Highway 42 in their honor — something she had been fighting for and working toward for years.

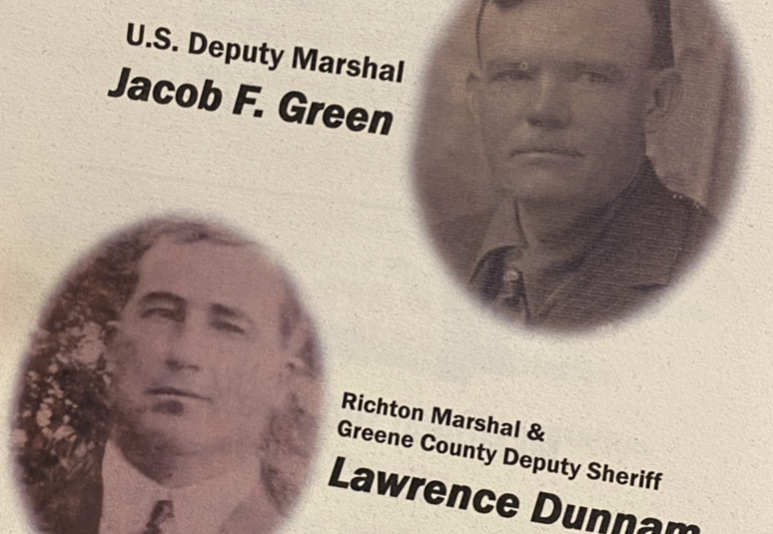

Green was a prohibition agent for the U.S. Marshals — now that unit is known as the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, or the ATF. Dunnam was not only a town marshal for Richton, he was also a Greene County deputy. The two, who were distant cousins, had worked together on prohibition cases in a time in history that was particularly deadly for prohibition agents.

After 14 months of working prohibition, Green was approached by Sid Baggett, a known bootlegger, who said he had knowledge of an active moonshine still. Baggett drew a map and put an X on the spot of where the still could be found in a swampy, densely-grown area just between Richton and Sandhill. He said it was run by a moonshiner named Henry Bond and his lackeys, Mancey Kelly, Johnny Adams, and Will Morris.

Dunnam had been recently involved in serving warrants on several of those men, and Green knew he would be the right backup to take when going to shut down the still. The two marshals called a taxi driver to take them to the closest spot on the road, and told him that if they didn’t return, to go get help. They set out on foot about six miles outside of Richton, carefully tracing their steps toward the X on Baggett’s map.

As Green and Dunnam approached the still, they could hear voices. As the story is told by Hollinghead, the moonshiners were talking about how they distrusted Baggett so much that they wouldn’t be surprised if Baggett “didn’t send Jake Green” in after them.

Green and Dunnam split up, ready to flank the still on both sides. The chaos erupted when Green yelled, “Hands up!”

Immediately Kelly and Dunnam began to trade shots and Kelly went down. Green was engaged in a shootout with Bond, who fell to the ground after Green shot him in the stomach.

Green turned to engage Adams as Bond sat up from where he lay and leveled his shotgun at the outgunned Green. Bond’s shot went down his pistol muzzle, disabling his gun and his hand, and left him with a fatal head wound.

Kelly had gotten away from the spot where he had fallen, and he had left his shotgun. Dunnam was shot by one of the others and went down on all fours. As he plead for his life, Adams picked up Kelly’s shotgun and put four blasts in his back.

Back at the taxi, the driver had heard the gunfire. He waited for about 30 minutes, and when the officers didn’t return, he went to the nearest home to call for help.

On April 2, 1921, a doctor was called to Bond’s home. He had a gunshot wound to the stomach that he told the doctor was a hunting accident. The doctor hadn’t heard of the shootings the night before, and had him taken to a hospital in Laurel.

Morris went with him, where he ended up confessing the previous night’s events to a Marshal. At that point, several citizens of Greene County armed themselves and went to the woods to bring Dunnam and Green home.

The struggle was evident when the bodies were found. Green’s pistol lay beside his body, and Dunnam’s was still tight in his grasp. The two, with their pistols, had gone up against two shotguns and a pistol. Morris had not been armed.

John W. Crowder and his son Edward took their mule wagon to the scene in order to bring the fallen officers out of the woods. They were taken from there to Dunnam’s home, and Green was later taken to his own house. The two were buried the next day.

Investigators began asking Kelly about the wound on his arm, Adams about the one on his hand, and Bond’s stomach wound spoke volumes as well. All three of them were arrested and taken to the jail in Hattiesburg.

District Attorney Martin Miller and Prohibition Agent in Charge Ellis Chapman promised justice for Green and Dunnam. All four moonshiners were indicted in the murder of both officers, as well as for making illegal moonshine. Baggett was indicted for providing the map that took Green and Dunnam to their deaths.

Adams turned state’s evidence in order to avoid the gallows. He would serve a life sentence, but the death surrounding that cursed night had yet to end.

Kelly used a concealed pocket knife to cut his throat on both sides and was dead soon after.

Bond appealed the case and lost. He then concocted a plan to escape from the jail and had his sister smuggle a pistol in by hiding it in a bag of tomatoes. He held on to it for a few days and then ambushed Hinds County Deputy and Detention Officer John Harris, who was a 10 year veteran.

Harris didn’t go lightly, returning fire and killing Bond, and then locking the cell and making it to the sheriff’s office before he died. He was 50 years old.

As Hollinghead stated in her address to the families of Green and Dunnam as well as to law enforcement from the agencies local to the area as well as some federal and state agencies, four wives became widows. Five men died senselessly over some moonshiners’ bad choices. Nineteen children — three Green’s, eight Dunnam’s, three Kelly’s, and five Bonds’ were left fatherless.

And yet their sacrifice will always be remembered. ATF Supervisory special agent Jason Denham reassured the families of both officers that, “Ten years, 20 years, 100 years to the families, just know from our agency’s standpoint, that means a lot… given the danger, the dedication to duty that Green and Dunnam showed was extraordinary, reminding us that for many, law enforcement is not a career, it’s a calling.”